Allegory is the expression of truths or generalizations about human existence by means of symbolic fictional figures, places or events.

Many readers have asked me about the allegories used in The Wisdom of the Flock.

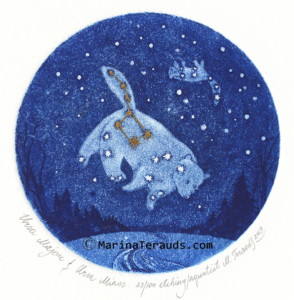

The Featured image for this post is entitled “Unsolved Mystery”. It is by Marina Terauds. Marina was gracious enough to agree to let me use it, and for that I thank her. If I could have figured out a way to use it as the cover of the book, it would have been there. Please visit Marina’s website and support her work – which is all wonderful: http://www.marinaterauds.com/index.htm

First and foremost, I believe is my primary allegory is the use of the flock of birds to symbolize the human subconscious – or perhaps better expressed as Carl Jung named it – the human “collective unconscious“.

An explanation can be found here: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-collective-unconscious-2671571

Jung believed that there are archetypal symbols that all humans know intuitively. He believed that these “understandings” were genetically inherited, but there are other theories as well. His book, Man and his Symbols, influenced me greatly.

The flock always seems to show up when one of the characters in The Wisdom of the Flock is going to experience something in the subconscious realm. Mesmer relied on the subconscious (even though he didn’t realize it) to effect his “cures” – the same way that we realize that hypnotism today taps into the subconscious mind.

https://www.elitedaily.com/life/culture/whats-really-happening-inside-brain-youre-hypnotized/2043096

This collective unconscious might cause us to naturally be afraid of snakes or high places. However, in the case of Marianne, tapping into the collective unconscious led to a type of “guided imagery” that she used to aid Mesmer. We might inherently understand things without having ever been taught them.

The science of altered states of consciousness can provide even more background on this allegory: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altered_state_of_consciousness for the interested reader. Another example that influenced me was the Ken Russell film Altered States – based on the novel by Paddy Chayefsky. OK, so my characters don’t “devolve” into primordial goo – but I always thought that was a little bit over the top anyway! The concept of using a method of transcendence (sensory deprivation in that case) to connect with the collective unconscious remains intriguing.

A few readers have asked me: Where is the place in the heavens where the Queen and Marianne meet? Once again, it is a place only within our common imagination, our collective unconscious. I tried to leave clues of the “non-reality” of the place by making it fanciful (e.g. the constellations come alive, people appear translucent, it is not cold, and people can breathe, etc.) but you must suspend reality to get there. Ben even visits this realm once, but he distrusts his own memory of it afterwards. Ben does need proof of things, after all.

Once again, I took inspiration from one of Marina Terauds prints:

Next, let’s talk about Love:

Love is a transcendent human emotion that we all (hopefully) experience, but none of us fully understand. Casanova is the character in The Wisdom of the Flock who discusses love most, and it is his mantra. But there are several allegories regarding love – and the way that it can change over time. There is the loving relationship of Ben and Marianne (waning), as well as the loving relationship between Ben and Minette (blossoming). And there is the marriage of Jacques and Marie-Therese Leray – where the fire has gone out. The allegory here is the changing nature of human love, played out through the characters in The Wisdom of the Flock. However, the theory that I have Casanova expound – that love is the reason that human society advances – instead of purely “procreating and dying” – I believe is inherently true. I realize that this is a very optimistic view of the world, so I hope that the future will bear me out.

Then there is the tension between Science and Mysticism (or perhaps pseudoscience is a better term). As one of my reviewers astutely noted, the situation is not so much different now, nearly 250 years later.

I think that the Foreword (taken from the Historical Introduction to the Report of Franklin’s Commission on Mesmerism) said it best:

Perhaps the history of the errors of mankind, all things considered, is more valuable and interesting than that of their discoveries. Truth is uniform and narrow; it constantly exists, and does not seem to require so much an active energy, as a passive aptitude of soul in order to encounter it. But error is endlessly diversified; it has no reality, but is the pure and simple creation of the mind that invents it. In this field the soul has room enough to expand herself, to display all her boundless faculties, and all her beautiful and interesting extravagancies and absurdities.

Or as a more modern quote (attributed to Mark Twain) put it: A Lie Can Travel Halfway Around the World While the Truth Is Putting On Its Shoes.

However you want to conceive it, the allegory used throughout the book is that people will believe Mesmer because they want to, not because he has proved the validity of his technique. The quest for truth is usually boring and holds none of the excitement of believing a in beautiful untruth. Same then as now.

Finally, let’s talk about independence and freedom. America was certainly undergoing a huge change while Ben was in France – and France itself was soon to undergo a major social upheaval as well. The characters in The Wisdom of the Flock (particularly Ben) do not seem to fully understand their significance in the “bigger picture” – but who does in their own time? Marie Antoinette seems to perceive her role, and there is some historical evidence that she did – although she was ultimately swept up in the French revolution and subsequently villianized (and executed) for her role as a part of the aristocracy. The role of the French in America’s quest for independence has never been fully appreciated or rewarded to this day. Ben seems conflicted in moments when he has to confront the social differences in late 18th century France. This is not much different than today, when many in America observe the disparities between the rich and the poor increasing every year.

Perhaps you see other allegories in The Wisdom of the Flock? If so, drop me a line and I’ll update this blog.