Portraits

of Ben Franklin

We are all familiar with Ben’s portrait on the 100-dollar bill:

This image comes from a H.B. Hall engraving of the Joseph-Siffred Duplessis portrait of an older Benjamin Franklin – and has been used on the $100 bill from 1996 onward.

But Franklin was also one of the most recognizable figures of his own time. He had many formal portraits done, but also etchings, drawings, busts, commemorative medallions, even full-sized statues made – both during his lifetime and after.

The book Benjamin Franklin in Portraiture by Charles Coleman Sellers, Yale University Press 1962 (unfortunately now out of print) contains a wealth of information about the artists who depicted Franklin and provides over 200 illustrations of the various art forms depicting him.

In addition to the voluminous original works of art, an entire cottage industry sprung up copying the originals for “mass production”. Interestingly, medallions seemed to be the most popular image in the late 1700’s – perhaps because nearly everyone could at least own an inexpensive reproduction.

One of the most famous medallions was made by Jean Baptiste Nini (1717-1786) and shows a profile of franklin wearing a fur cap:

Note that this is a much different cap than that shown in my separate blog post regarding Ben’s famous fur cap. The artist, Jean-Baptiste Nini, was employed by Jacques Le Ray and worked at his chateau in Chaumont, far from Passy. There is a story that Le Ray requested the medallion of Franklin with a fur cap – but Nini had never seen the one Ben actually wore. He therefore portrayed Rousseau’s cap instead on Ben’s head.

https://www.fi.edu/history-resources/nini-medallion

On the left above is an original 1777 terra cotta (also called faience – or tin glazed earthenware) Nini-produced medallion based on a drawing by Thomas Walpole, and on the right a ceramic copy of the Nini original. Smaller versions of the medallion could be worn on a ribbon or chain around the neck or tucked into a pocket and rubbed for good luck!

Franklins image came in all forms and sizes. In a letter to his daughter Sarah Bache, dated June 3rd, 1779, Ben wrote from Passy, France:

…The clay medallion of me you say you gave to Mr. Hopkinson was the first of the kind made in France. A variety of others have been made since of different sizes; some to be set in lids of snuff boxes, and some so small as to be worn in rings; and the numbers sold are incredible. These, with the pictures, busts, and prints, (of which copies upon copies are spread every where) have made your father’s face as well known as that of the moon, so that he durst not do anything that would oblige him to run away, as his phiz would discover him wherever he should venture to show it. It is said by learned etymologists that the name Doll, for the images children play with, is derived from the word IDOL; from the number of dolls now made of him, he may be truly said, in that sense, to be i-doll-ized in this country…

In addition to these popular “idols”, Ben sat for many formal portraits as a well-to-do older man. Unfortunately, there are very few images of Ben as a young man – most likely because it cost a lot to have your portrait drawn in the 1700’s. Ben was not rich as a young man.

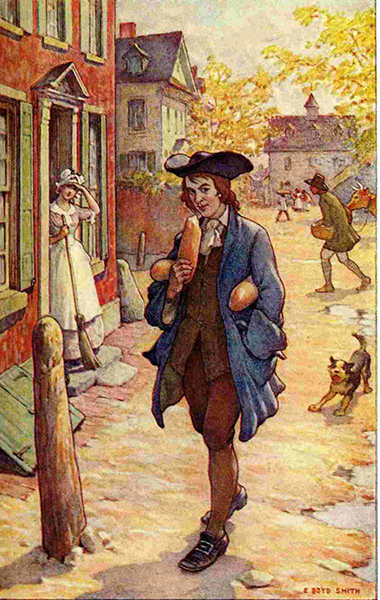

Many images of what artists thought Ben might have looked like as a young man do exist, but they were usually romanticized drawings of him working diligently as a printer’s apprentice, flying a kite in a thunderstorm, etc.

The 1916 printing of Ben’s autobiography, with beautiful illustrations by E. Boyd Smith, shows the artist’s rendition of many of these scenes.

In the following dramatized scene, Ben has recently returned to Philadelphia from London and is being ogled by his future wife Deborah:

This book has been digitized by the Gutenberg Project and is available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm

This next portrait of Franklin, done by Richard Feke in 1746, painted during the time that Ben was recently retired as a successful printer in Philadelphia, is one of the few that was done contemporaneously. He would have been about 40 years old at the time.

Attribution: Wikimedia Commons.

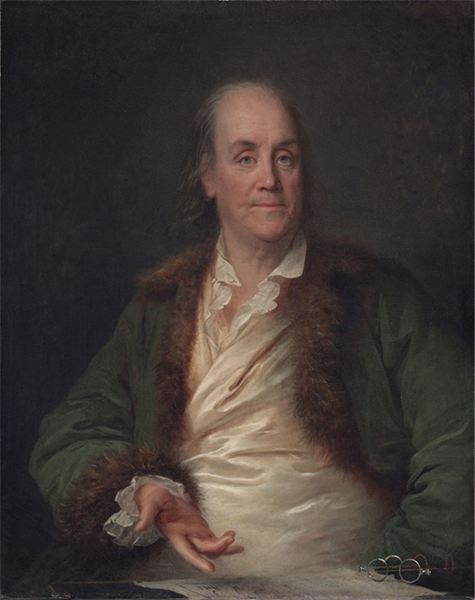

One of the most well-known portraits of Ben was painted by Joseph Siffred Duplessis in 1778 (and first displayed publicly in 1779) and serves to introduce our hero at the beginning of The Wisdom of the Flock.

It is entitled “Vir” – from the Latin word meaning a brave or courageous man – but also the root of the English word virile.

There were actually several versions of this portrait (as many as eight), and one showing Ben without a fur collar was reportedly once owned by Thomas Jefferson.

While Ben certainly looks very “virile” in this portrait, it is not my favorite. That honor would go to the much less formal and much more intimate one painted by Anne Rosalie Filleul (1752-1794).

I call this portrait, “Ben trying to look sexy”, but my wife doesn’t think so. Attribution: Wikimedia Commons.

Still, I believe that Ms. Filleul captured a very warm, open, and personal expression on Ben as compared to the stiff, almost annoyed or put out, expression he wears for Duplessis in Vir.

Some Franklin portraits relate to specific events or accomplishments:

This line engraving by F. D. Née after L. G. de Carmontelle dates from 1780, and is inscribed: We saw him disarm the Tyrants and the Gods – to recognize his role in the American revolution and his pioneering scientific work with electricity. Attribution: Wellcome Collection.

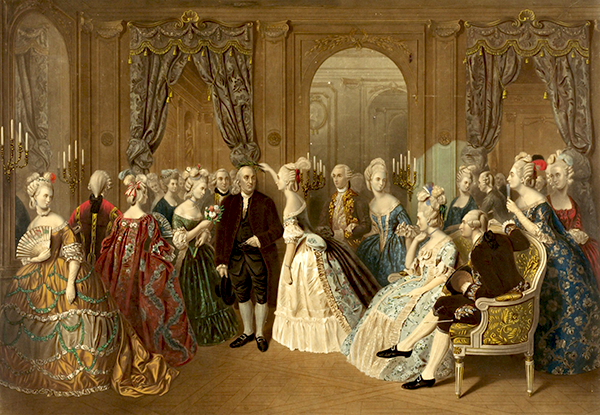

Next is an illustration that evokes a scene portrayed in The Wisdom of the Flock. It is one where Ben is coronated with a laurel wreath by Queen Marie Antoinette at Versailles as recognition of the American victories over the British. The date of the event in the book is March 1783 and this illustration purportedly shows Ben’s royal reception in 1778, but it gives us a glimpse of French royalty and their fascination with Ben.

Franklin’s Reception at the Court of France. Lithograph, hand colored. Hohenstein, Anton (originally published in 1860’s). Attribution: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

Another scene portrayed in The Wisdom of the Flock is the signing of the Treaty of Paris – and the unintentionally unfinished portrait by Benjamin West to commemorate it.

Treaty of Paris (unfinished). Oil on Canvas. Benjamin West. 1783 From left to right: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and William Temple Franklin. Attribution: Wikimedia Commons.

David Hartley was the British representative to the signing, and was scheduled to sit for his portrait, but unexpectedly left prior to doing so. There is some controversy over whether he “refused” or he simply departed without sitting for his portrait – most historians believe the latter to be true. Nonetheless, the result was the same – the picture was never finished.

Another Benjamin West portrait, done after Ben’s death, is more romanticized.

Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky. Benjamin West, 1816. Attribution: Wikimedia Commons.

While not a scene that ever really happened, of course – he probably would have been electrocuted as it is portrayed – this image exemplifies how Ben was idolized both during his lifetime and after.

Franklin is often portrayed as being studious:

This portrait by David Martin (done in 1766) pre-dates Franklin’s time in France. The bust facing Ben is of Isaac Newton. He seems to have even still had almost a full head of hair at that point, or the artist was being kind. This painting now hangs in the White House. Attribution: Wikimedia Commons.

Franklin was the subject of another illustration that became a chapter in The Wisdom of the Flock. He was a member of the Masonic Lodge first in America, and then while living in England, and also during his stay in France. He achieved the level of Grand Master at an early age (1735) and was elected as Worshipful Master (W.M.) of the Lodge of the Nine Sisters in Paris in 1782.

This engraving by Kurz & Allison, Chicago, published in 1896, depicts Franklin in his Masonic regalia, similar to what he might have worn while delivering his eulogy for Voltaire in the Paris Lodge. Attribution: Public Domain. Copyrighted 1896 by Kurz & Allison, 76-78 Wabash Avenue, Chicago.

Franklin’s Masonic chronology can be found here:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20085334

Perhaps one of the largest and most impressive images of Franklin now stands (or probably more accurately, I should say sits) in the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial, located in The Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was sculpted by James Earle Frazier and dedicated in 1938. It is 20 feet tall and weighs 27 tons.

Clearly, Ben was a larger than life figure in both his own lifetime and now! Attribution: Wikipedia Commons.